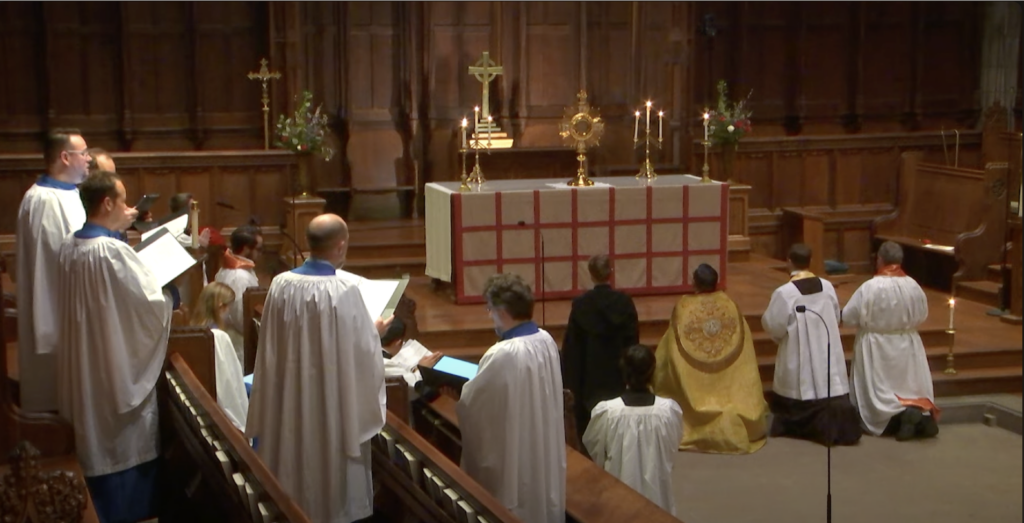

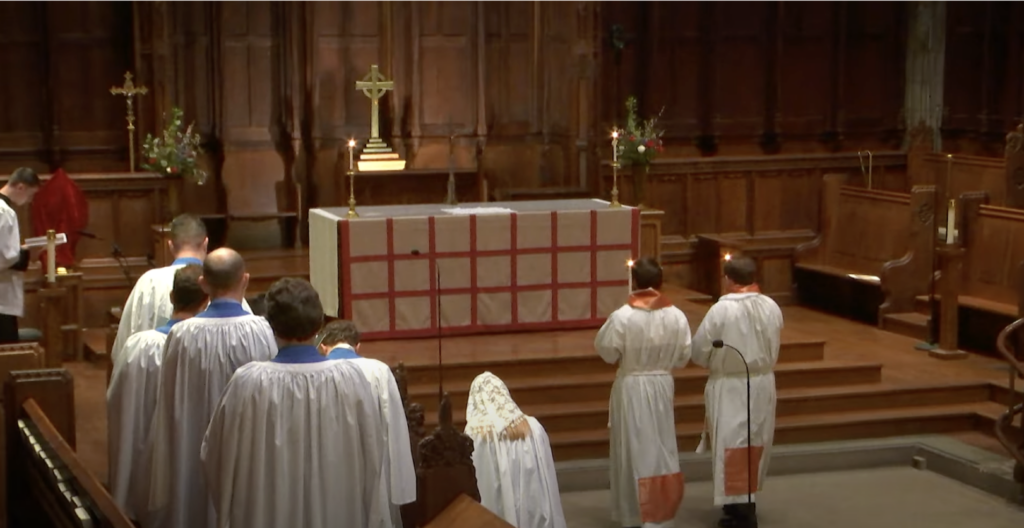

1,000 people experienced Sarum Vespers and Eucharistic Adoration at Princeton University’s chapel on Friday, March 1, 2024, co-hosted by Scala Foundation. Phenomenal music, spectacular art, reverent liturgy, and three educational talks brought together people of all ages, cultures, and faith backgrounds. (see David Clayton’s blog post for links to the videos of the events.)

Since 1998, I have worshipped in small groups of 100-200 people in that chapel. I’ve also attended packed, loud graduation ceremonies there. But never had I experienced so much reverence and joy. Incense pervaded the chapel, awakening our senses and illuminating our memories. The service was not merely captivating; it was participatory. For an hour and a half, we stood, sat, knelt, and sang in unison. We followed along with a beautiful program filled with images of sacred art commissioned specifically for this event, organized by Peter Carter of the Catholic Sacred Music Project and musical director of the Aquinas Institute at Princeton University.

One participant at the Vespers, a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary and a pastor of an Episcopal Church that practices Evensong, which is, in his words, a “liturgical cousin” of Sarum Vespers, noted how “all the participants moved without distraction or attraction to individuals—the flow was as it should be to direct glory to God.”

This is a new phenomenon. What might at other times have been seen as an obscure throw-back to dated medieval times became, on this occasion, something fresh and new with participation from people of different ages, faiths and backgrounds. It is a sign that a larger cultural renewal is happening. Organist Clara Gerdes Bartz opened the service, calling our attention to the sacred event. The music, led by Gallicantus, a world-renowned ensemble specializing in early music, set the tenor of the evening as one of authentic worship. One high school student who participated said, “I felt lifted and light as if the world had paused for a moment, and all I could hear was the sound of the organ and the chanting.”

Before the service began, three people dedicated to reviving beautiful culture shared their insights to prepare us for what we were about to experience. James Griffin from the Durandis Institute discussed the ‘Sarum Use of the Roman Rite,’ which originated in the Cathedral of Salisbury, England, in the 1500s. The forms of the chant and the processions have been preserved in contemporary liturgical worship in the Anglican Church in England and the Ordinariate in the United States and UK.

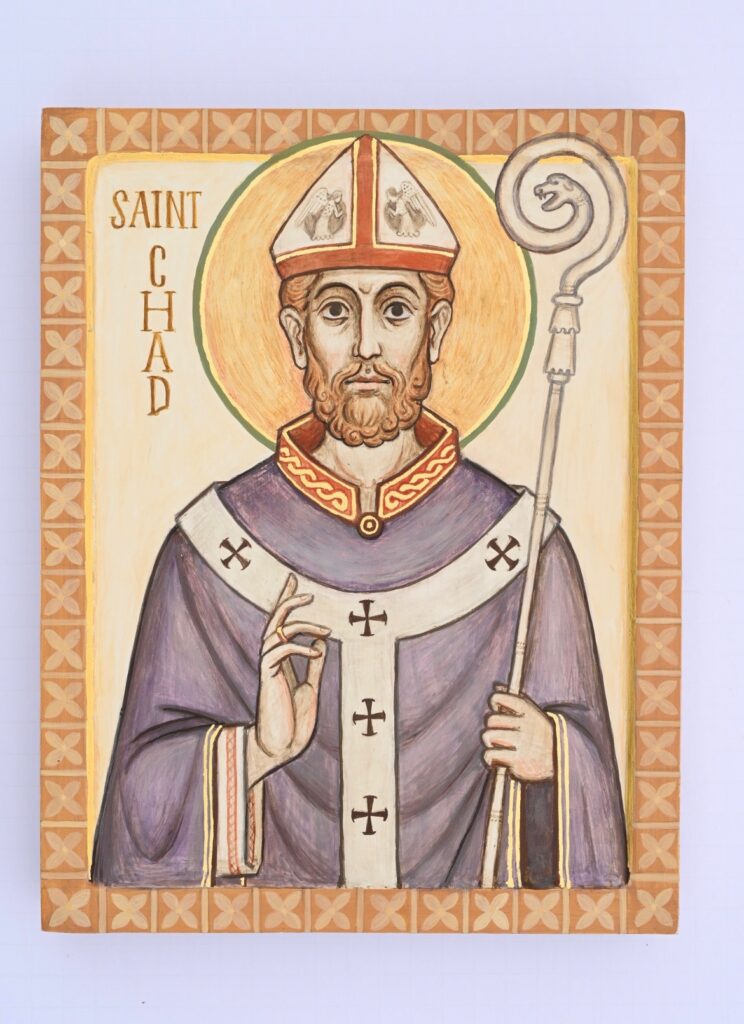

Liturgical artist David Clayton of Pontifex University and Scala Foundation highlighted the importance of sacred images during prayer. He explained how,

“Sacred art shows us what we do not see with our eyes in the here and now. It portrays the saints and angels praying with us in heaven eternally. It illuminates the truths behind the actions of the liturgy and focuses our attention on what is important at any given time in our worship…The art we choose conforms to a style developed gradually over generations and centuries, going back to the early Church, to fulfill its purpose well, which is to aid us in deep participation in the worship of God… The Church, in her wisdom, observes the fruits of that worship…Getting this right takes patience and careful observation of many iterations of style.”

David personally commissioned two new pieces of art for the service. He asked two artists, Ioana Belcea and Ander Scharbach, to combine their personal inspiration with “the English gothic style of the School of St Albans of the 13th century, a period when the Sarum Use liturgy was at its height. This tradition of sacred art is characterized by the description of form with the elegant flow of line, a limited palette with muted color, and by having ornate, patterned borders.” The result, as he said, was art was universal in its appeal: “Everyone in 13th-century England would have been able to relate to the images every bit as much as the worshipers in 21st-century America, who excitedly mobbed the artists after the Vespers were over, to ask about the beautiful icons they had seen. This is because the art conforms to traditional principles of liturgical art, which are universal.”

Gabriel Crouch, the Director of Music at the Princeton University Chapel and choir director of Gallicantus, a UK-based choir specializing in early music, gave a detailed history of the hymns we would hear and the musical form, emphasizing that the experience was meant to be a shared prayer, not a concert. He commented,

“What an enormous honor it is for us to be involved in this event and to be able to translate our love and immersion in this music that we have venerated all our lives into practical use for which this music was written. This was not something I thought I’d ever be able to be involved with. It’s very meaningful for us to sing this music not in a concert context but in a liturgical context, the context the composers would have preferred it be heard.”

As a Roman Catholic teaching at a Protestant seminary, I’ve experienced beautiful, shared worship among Christians of different denominations, such as when focusing on the Liturgy of the Hours or the chanting of the Psalms. This practice is maintained in Orthodox churches, Eastern Rite Catholic churches, and many Roman Catholic monasteries such as the Benedictines. Like other events I’ve hosted through Scala Foundation, people were drawn into the chant more than anticipated.

The service concluded with a Eucharistic procession and adoration. The congregation knelt while Gallicantus chanted a 10-minute litany of the saints. A Lutheran student from Princeton Theological Seminary was particularly moved by the litany and commented how wonderful it would be to chant it on days other than All Saints’ Day or at funerals. Perhaps it was the closeness of the congregation to each other and to the saints that led several people to comment that being there felt like heaven.

A new generation of composers capable of creating music of the quality of Thomas Tallis or painters whose sacred art will evoke Fra Angelico will only emerge when we train people in these beautiful traditions and commission new works of art and music. We need to experience the masters occasionally so that when we worship at home and in local churches, we understand that we are partaking in this beautiful tradition.

Our culture yearns for the joy derived from shared worship—the knowledge that we can persist in our worldly struggles, comforted by God’s presence. Despite our differences, we unite to worship God, rejoicing in his beauty and holiness manifested in art and music. Participating in divine worship transforms us internally, preparing us to further contribute to the common good in our individual lives.

One young woman who attended the Vespers commented, “Being fully immersed in ethereal music and prayer brought both peace and excitement. I enjoyed following along and joining in the prayers and songs. Being surrounded by astounding music, architecture, and works of art brings such wonder; you can’t help but feel inspired and joyful.”

Another young man wrote, “I felt at peace. Any struggles or problems all fled my mind. My focus was directed at one thing only: the Divine. It felt as though it was impossible to think about something else amidst something as beautiful as that ceremony.”

Yet another young person said, “While I was listening to the Vespers, it made me feel motivated to do something I would not usually feel like doing. It inspired me to want to pray to God.”

The openness to rich traditions of culture and liturgy that can transform hearts and our nation is evidence that the next great awakening in America is underway.

From the Benediction | common good | Educating For Beauty & Wisdom | Margarita Mooney Clayton | Princeton | Sacred Art | Sarum | Vespers series

View more Posts