In a recently posted an article I discussed the legitimacy of representing Christ or Our Lady as an ethnicity that is not historically accurate. In this post I want to consider situations when it might not be appropriate. Consider first some well known, relatively contemporary examples: a series painted by a Japanese Discalced Carmelite nun in a Carmelite convent in Japan.

It is apparent to all that these are not historically accurate images. The question as to their appropriateness relates to who is going to see these images, on the whole; and will the painting communicate to those people the theological truths that are connected with images of Our Lady and Our Lord. Deviating from historical accuracy will always require some compromise whereby it is felt that what is lost is more than made up by the gains in communicating the gospel. In this regard, it occurs to me contemporary Japanese are not so parochial as to jusify such images. Perhaps I am wrong on this, I am certainly no expert on Japanese culture, but I would imagine that Japanese people are well aware of what people from the eastern Mediterranean would have likely looked like 2,000 years ago and so an historically accurate representation, informed by Christian tradition, would not alienate any Japanese observers. Given that it always better to be accurate if you can, for all the charm of these images, I might have counselled against painting them, if I were asked today. It is of course, ultimately, a matter for those who commissioned them to decide. I have little doubt that the intentions of this artist were good.

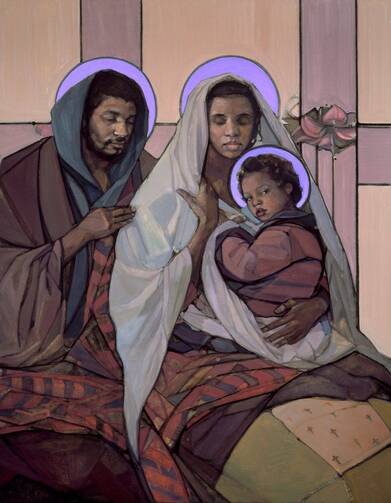

Here is something a bit different and which raises different questions.

It is the depiction of an African American Christ by the American artist Janet McKenzie. As to the validity of its use as sacred art, I would I think, make the same argument as with the Japanese images: that even if the intended audience is predominantly African American (or any others of African descent) the best sort of image for communicating the gospel would not be an African American Christ but rather a more historically accurate depiction. This is because on the whole African Americans, in common with most other Americans, are aware of what people from the eastern mediterranean look like. So again, for all the beauty and power of these paintings, if asked I would against using such an image as sacred art.

There is another argument to be made here, which addresses another, more disturbing, possible reason for painting this. There is a review of the painting posted on the artist’s website from National Geographic which says the following:

For twenty years Janet McKenzie’s Jesus of the People has moved across the world serving as an image of inclusion, hope and love. This iconic painting – a force for good – challenges racial prejudice and social injustice by reminding and celebrating that we are all created equally and beautifully in God’s likeness.

This looks suspiciously like standard ‘woke’messaging of Critical Race Theory, which is a late 20th century iteration of Marxist theory. This being the case, for all the language of inclusion, then the intention is not to be inclusive but rather to undermine the Church and Christianity by causing division. The Marxist interpretation of history includes the idea that modern society is bad because it is the product of Christianity, which is a tool for power exercised by the white patriarchy. The Christ of traditional Christianity is traditionally portrayed as a white and Western European, so the argument runs, in order to promote and uphold power of the controlling group. This assertion about Christian art is false, I have argued here, as is not backed up by history (see The Woke Fallacy That Christianity Traditionally Portrays Christ as a White European). Nevertheless, consistent with this flawed view, the message of this painting is one of an inclusion that is open to all except, that is, for white men. It is therefore in fact highly exclusionary. For the woke Marxist, such a painting would be intended to communicate to all people who see it, regardless of race, that Christ was not white on the false assumption that Christianity propogates the idea of a white Christ iin order to promote an oppressive power structure. The goal is not justice, but rather to incite anger and violence, by pitting all minorities against the supposed oppressors who are the ‘white patriarcy’.

We should be clear, the wider goal of Marxism is not to eliminate injustice from society through the transformation of Christianity, but rather seek the total destruction of both contemporary society and Christianity. By their theory, this will then usher in the spontaneous emergence of a new just society untainted by Christianity (a staggeringly superstitious idea that has no basis in reason). Their method is to infiltrate institutions and then to cause division, and ultimately their destruction through violence. By this theory conflict and violence is a necessary component of the required destruction, and therefore resentment and anger should be stoked. If a publication such as National Geographic is championing this painting, then it suggests to me that they at least believe it furthers the Marxist cause. Not all who go along with the woke rhetoric are aware of the ultimate goals of those who formulated the theories and so have become unwitting agents of these evil forces.

Elsewhere, the artist is quoted as saying:

My art presents Jesus and Mary and many others in diverse ways because the essence of Jesus is about inclusion, not exclusion. Every one of us is created beautifully, mysteriously and equally in God’s likeness.

One implication of this statement might be that in the view of the artist, using traditional portrayals of Christ is bad and exclusionary, otherwise why not conform to tradition? This view, which I disagree with strongly, is consistent with the Marxist critique of Christianity and traditional Christian art.

I will let the readers decide for themselves on whether these paintings are good or bad or if there is a risk of their propogating anti-Christian Marxist propoganda. In the meantime, here is an ancient Coptic painting, dating from the 6th century. It originates from Africa and was painted when the West was a cultural backwater and white patrimony was even a thing.

From the David Clayton | Janet McKenzie | Marxism | Post Modernism | Sacred Art series

View more Posts