This article was originally written for the May-June edition of Angelus Magazine

When one has a conservative mindset, as I do, tradition plays an important part in the consideration of how things ought to be today. To my mind, conservatives are not against change altogether – clearly we acknowledge that new challenges have to be addressed and the past cannot always give us the best answer. However, the first question that is asked when addressing any situation is, how did people who thought like us deal with this in the past? Then, assuming that there is no compelling reason to change, we try first the approaches used in the past.

In the context of Catholic sacred art, there are three well established traditions that have emerged since the Church was established and which I consider to be authentic styles. The first is the iconographic style, the second is the gothic and the third is the baroque (the style of the Catholic Counter-Reformation that had its high-point in the 17th century.

We live in an age in which, separated from our artistic traditions, there is no consensus on the artistic style that is appropriate for the liturgy today. Consequently, every time art is commissioned for a church setting, a conscious choice has to be made as to what style is appropriate. Do we choose one of those from the past, or perhaps we should think about choosing a new style?

I argued recently in my blog thewayofbeauty.org that my personal choice in these situations, especially in America, would be a form of the gothic style. I would like to see the development of a 21st century neo-gothic culture that is driven by the wellspring of all Catholic culture, the liturgy.

However before making that conclusion I did consider the possibility of something new. As a conservative, I must acknowledge that one of the lessons of the past is that on occasion it is appropriate to start afresh. Clearly, Catholics in the 12th century thought so when establishing the gothic style; just as Catholics in the 16th century thought so when establishing the baroque style as part of their cultural response to the Reformation, and guided by the directives of the Council of Trent. So to make an informed choice today it is good to understand how each of these traditions was established to consider the possibility that we need a fourth, new tradition to be established today. I have discussed the emergence of the gothic and the baroque in my book The Way of Beauty. In this article I will give a broad overview of the emergence of the first of these styles, the iconographic style.

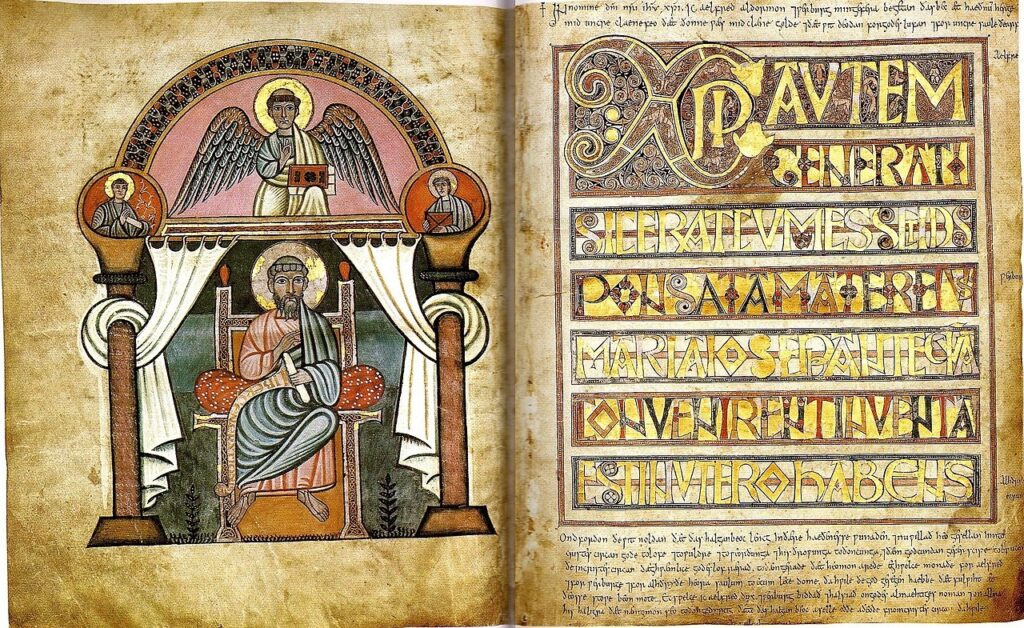

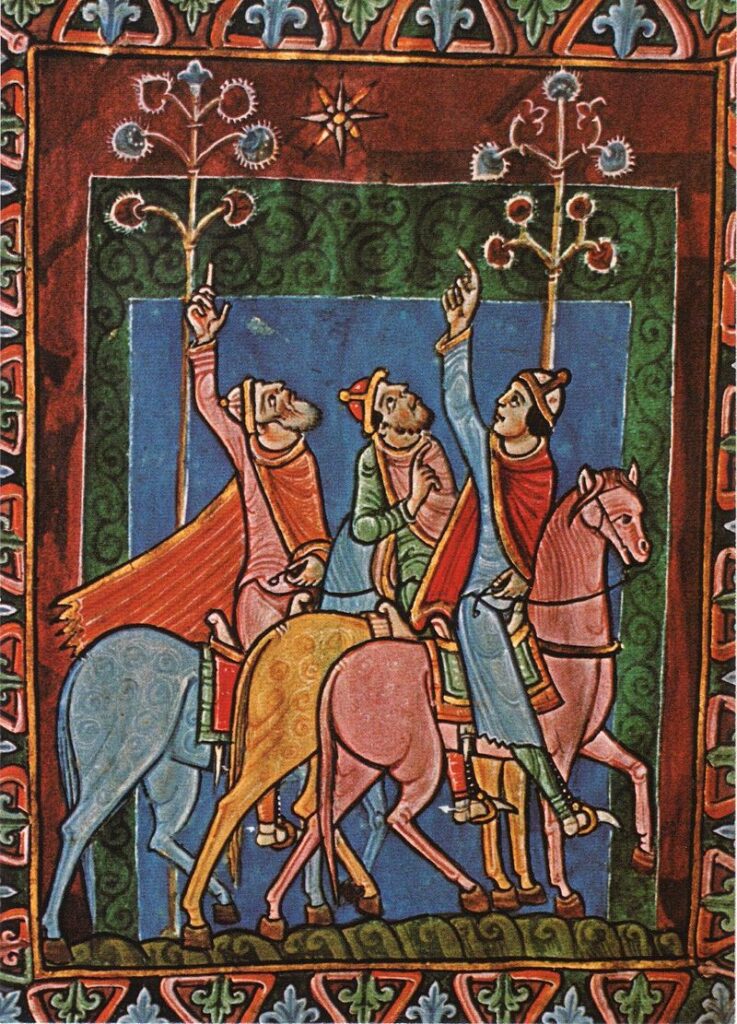

When we speak of icons today, we tend to think of the style of art that characterizes the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox Churches, and primarily Russian and Greek icons. However, the essential elements of this style were established in the Christian world in about the 5th century and became the standard for all Christian art from West to East in a very short period of time. There were local variations in style and changes over time, but for centuries none discarded the essential elements of the iconographic style. In the West, the styles that art historians today would refer to as Anglo-Saxon, Irish Celtic, Carolingian, Ottonian and Romanesque are all variants on the iconographic style.

Before we discuss the process of the emergence of this style in the early Church it is worth reflecting on what makes any style the standard. In some ways this is a mystery that I cannot claim to explain fully, but some characteristics do seem to apply. First, I am not aware of any statements invoking papal authority and mandating particular styles of art in the Roman Church. The Seventh Ecumenical Council, which articulated a theology of images did not specify a style, and neither have any popes since, except in the broadest, general terms (Pius XII in Mediator Dei comes to mind). Rather, we see a dynamic interplay of the two effects, both operating in each local Christian community. First, patrons – likely local clergy or bishops – paid for the art and commissioned it, and second is the popular taste of those who saw the art in the churches once it was commissioned. .

In the proper order of things, the art is chosen for its beauty and suitability for its sacred purpose, and for the perceived impact that it might have on the spiritual lives of the faithful. This works best for those clergy whose influence or authority is localized so that they have direct contact with the people whose lives their decisions affect. Therefore, the signals of approval that they are looking for relate more to the effect on their flock, rather than the approval of their superiors or peers.

However, once art was commissioned for a local community, it is clear that there was sufficient communication between communities across the Christian world for some for others, sometimes even thousands of miles away to learn from good examples. The resulting artistic style is a blend of foundational universal principles overlaid with local and temporal variations. The universal elements of good Christian traditional art both reflect and in turn guide the natural desire of all men for supernatural fulfillment in the Common Good; while the local and temporal variations, which are more superficial but nevertheless also necessary, reflect more individual responses to that call as affected by local cultures.

Through this mechanism, a characteristic tradition emerges gradually. There is a constant process of modification and adaptation so as to improve it until there is a form that is recognized as having the desired impact on all the faithful. There is no guarantee that this will produce something good, of course, but this pattern of bottom up and lateral communication does seem to stand a better chance of producing something beautiful and permanent that will be passed onto future generations, than one imposed by a distant and central authority. In the ideal, this iterative process is guided by God, whose influence is strongest when all the actors in this scenario are formed in an authentic and orthodox liturgy. In fact, I would go so far as to say that without authentic liturgy, there is no authentic Catholic sacred art, and indeed, no authentic Catholic culture. The liturgy is the wellspring of Catholic culture.

Prior to Constantine’s proclamation of the toleration of the Christianity in the first part of the 4th century, Christianity was an underground movement and so the creation of public works of art was, for the most part, dangerous and therefore rare. There are some examples of figurative art from this period, such as from the Roman catacombs, but assuming what we see today is representative of what existed then, there was not yet enough art produced, to allow the emergence of a dominant style. When Christians could worship openly, after 313 AD (with a few later interruptions) it became much easier to create large scale and a greater number of works of art that allowed the dialectic I describe above to occur organically.

When there is an authentic growth of a Catholic art, the style of the representation is governed primarily by the way in which Christ is portrayed. So, considering the portrayals of Christ over this period: the first art produced reflected the existing style of Roman art, but in time this develops as artists grapple with the task of revealing Christ in both his humanity and divinity. This would be no easy task at the best of times, but given that the understanding of Christ as one person and two natures was developing simultaneously, this made the task doubly difficult as they were, to some degree, basing their art on an evolving understanding of who Christ was. The artist reveals invisible truths, such as a human soul or a divine nature, by imbuing the image with a symbolic quality. In seeking how to create an image that communicates the desired truths, he must balance naturalism – conformity to natural appearances – with idealism. Idealism in art is a process of partial abstraction, a controlled deviation from natural appearances that suggests to the viewer truths that are in reality invisible. The formula of how Christ was both human and divine was not worked out until the Fourth Ecumenical Council in the 5th century, and even then it was only broad terms so that disagreements over some of its implications were not resolved until the Sixth Ecumenical in the seventh century. It is instructive to note that it was not until after this, at the Seventh Ecumenical Council in the eighth century that a firm theology of images was established.

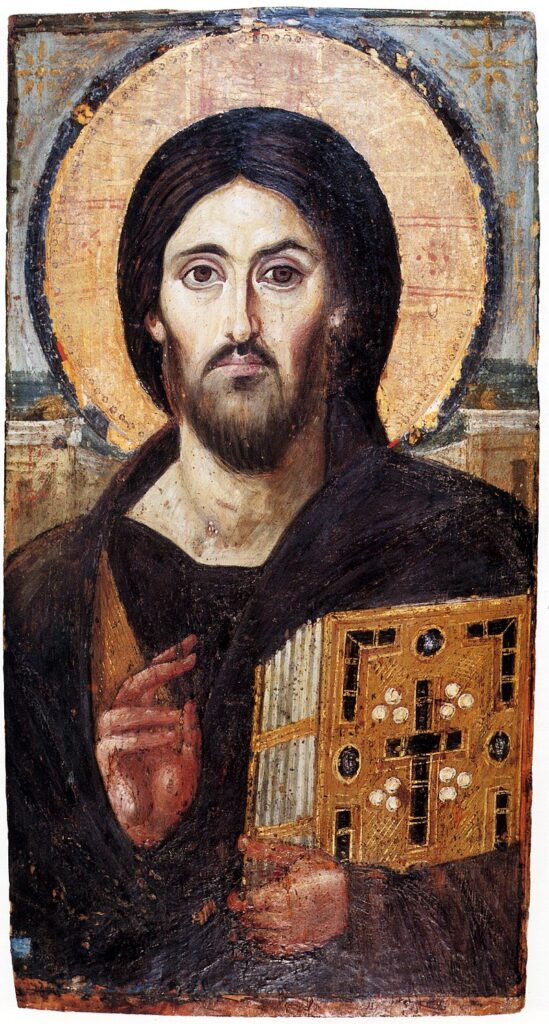

By the 5th century, then, we start to see an established style for the representation of Christ that becomes, broadly speaking, the prototype from then onwards. The image shown here is the oldest known example of Christ Pantocrator, the ‘blessing Christ ‘ – his hand gesture indicates the blessing. Scholars suggest that It was probably painted in Constantinople in the 6th century in a medium called encaustic. Encaustic is a paint that is made by suspending the colored pigment in hot wax, which is then brushed on while warm and liquid, setting once it cools.

There are two aspects of this image to discuss. First is the content, and second is the form, that is style.

Content first. What strikes me is how the man portrayed corresponds to what has become the standard image of Christ for centuries since and which still dominates today, with long, straight, and dark hair, a beard and mustache, and dark eyes. It should be noted that this originates in the Eastern Mediterranean and pre-dates the emergence of Western Europe as any sort of cultural force by centuries. Its existence therefore undermines the argument that the standard image of Christ is a construct of the white male patriarchy of Western Europe. Those who painted this will almost certainly have been accustomed to seeing people from the Holy Land. I suggest that they painted him this way because they believed, guided by tradition, that this is what Christ actually looked like. Some may be surprised at the lightness of the skin. Surely, one might say, the image should have the olive brown skin of the people from this region. Indeed, many icons from this time onwards, even those painted much later in Russia did show him with much darker skin, so this particular icon is unusually light compared with what later became the standard.

My suggestion as to why this might be is – and here I am assuming that the reproduction accurately reflects the original image, and that the artist was in full control of his medium – is that the skin is lightened to suggest a theological point ( and this is where we come to the consideration of the stylistic elements of icons). The theology of icons says that Christ and the saints who partake of his divine nature, are the source of their own ‘uncreated’ light. The halo is a conventional way of indicating this, but perhaps this artist wanted to reinforce the point and painted the figure so that the face emitted light as well. Another way of suggesting this principle in operation visually is to omit any reflected glint in the eye. Both of these other devices are included in this icon. One thing is pretty certain, this artist did not seek to portray Christ as a caucasian, Anglo-Saxon man. We do not see blond hair or blue eyes!

Commentators often refer to the fact that the expressions in each half of the face of this icon are different, arising from the differing slope in each eyebrow. This is done, it is suggested by some, to symbolize the two natures, one divine and one human present in this single person. This might be so. When I was learning iconography my teacher taught me to create an enigmatic expression by making one eye stern and the other calm and contented, again through the device of the differing eyebrows. The reason given by my instructor was to indicate that Christ is a judge whom we will meet on the last day, who is simultaneously just and merciful. The stern part of the expression indicated judgment, while the more compassionate one indicated mercy. I was taught to make the difference more subtle than we see here. To my mind this artist has created such a contrast that it is to some degree unsettling. I’m glad that subsequent artists were more nuanced in this regard.

Another standard iconographic stylistic device is the use of reverse perspective by which objects become larger in the distance. We see this in the gospel book. The use of reverse perspective is deliberate – conventional perspective was known at the time as it was a device used by pagan Roman artists. The use of reverse perspective helps the artist to communicate as a sense of the eschaton, that is our heavenly destiny. First, it creates an impression that is in some way otherworldly through its unnatural look, second it allows the artist to eliminate the illusion of depth in the painting. A well painted icon portrays an image that lives, so to speak and for the most part, in the plane of the painting, so indicating the heavenly realm which is outside time and space.

These characteristics remain, for the most part, in icons painted today.

The lesson I learn from this regarding the painting of art for today, is that if a new and dominant sacred art form emerges, it will not be because any one person (not even me!) nominates the style. Rather it will emerge gradually as the preferred choice of those communities of Catholics whose liturgical worship and faith are orthodox and who engage with art fruitfully during their participation in the liturgy. Only time will tell.

In the meantime, I’m still pushing for people to consider 21st century American neo-gothic in the hope that it catches on!

From the Beauty | common good | David Clayton | Sacred Art series

View more Posts