During my research for my book Faith Makes Us Live: Surviving and Thriving in the Haitian Diaspora, I met Stephanie in the English class for Haitians I helped tutor in Miami. She was always joyful and smiling, but when I asked her why she migrated to the U.S., I heard a harrowing story. In Haiti, Stephanie ran an agricultural cooperative near her hometown of Jacmel. When she refused to get all her workers to vote for a particular presidential candidate, a group of men broke into her house and raped her.

After telling me her painful story, she wiped her tears and a look of joy came over her face as she described how these horrible experiences didn’t change what she had been taught: to love everyone, even those with more money, or from other racial or ethnic groups, even those who are your enemies. She said:

“People who do bad things, like the people who burned my car, they know when they are doing something wrong. So it is up to God to touch their hearts and change them. If someone hurts you, you have to pray for them. If someone hates you, you have to love them.”

In Faith Makes Us Live, I used Stephanie as an example of what I called a theology of grace and hope at Notre Dame. Yes, the church’s social services were very important to Haitians who wanted to learn English, get a job, and get asylum papers, but just as important was their spiritual healing, as exemplified by Stephanie. When I made that argument to academic sociology audiences, some were sympathetic, having themselves seen powerful examples of people surpassing the evil they encounter and pouring love back into the world.

But others seemed to think the goal of sociology was to explain away Stephanie’s religious motivation by pointing to something psychological. The argument went like this: no one can know if God is real, but since Stephanie had been taught to believe in God, her socially constructed belief could have a real effect on her psychological happiness.

But is it really accurate to describe Stephanie’s forgiveness of those who harmed her, even desiring their conversion back to God, simply as a means to improve her own psychological well-being?

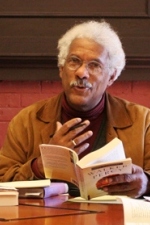

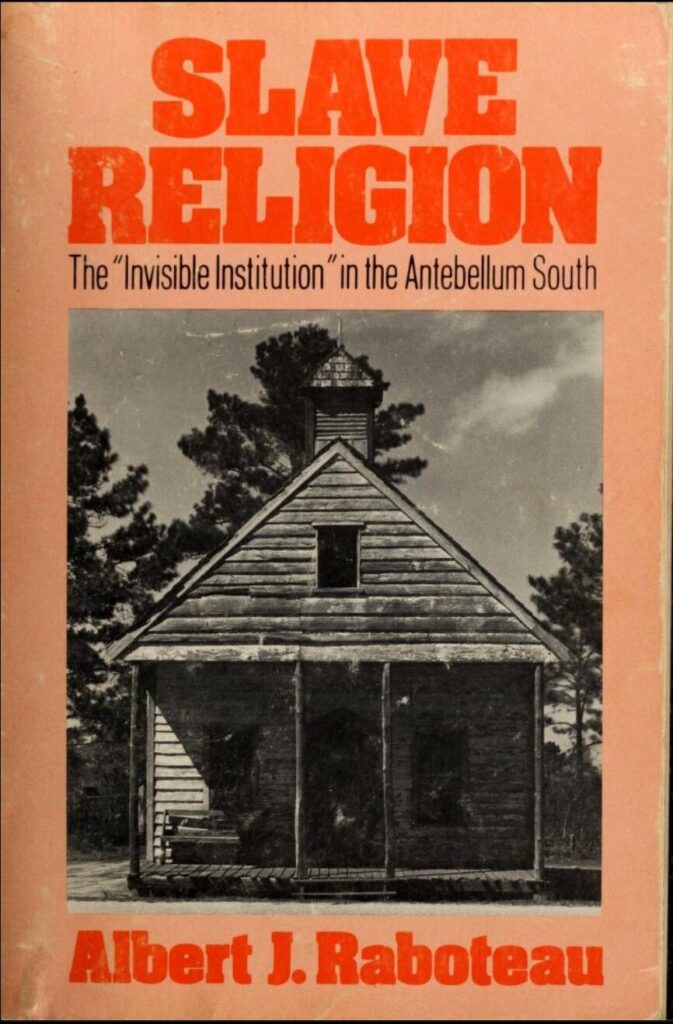

One morning in 2015 over coffee in Princeton, I shared this story with Albert Raboteau, the esteemed Professor of African-American Religion at Princeton University. In his book Slave Religion, Al argues that many historians had looked at religious belief and worship among slaves as either influences that lead either to rebellion or docility. But resistance or accommodation to conditions of slavery were not the only two options. Al described a third way which seemed similar to what I experienced among Haitians. In Slave Religion, Al described “a religious agency of a very real and powerful sort.” Slaves’ conversion experiences truly injected a feeling of new life in them, and their religious worship expressed the movement from sorrow to joy, from damnation to election. For example, Al wrote that “the meaning [of the Negro spirituals] was not so much an answer to the problem of suffering as the acceptance of the sorrow and the joy inherent in the human condition and an affirmation that life in itself was valuable.”

Through authentic religious conversion, and through participation in liturgy, through singing songs, and through experiences of God’s presence in their souls, the divine entered into human history. In Slave Religion, Al described how “people who had been through fire and ‘refined like gold’ reveal the capability of the human spirit not only to endure bitter suffering but also to resist and even transcend the persistent attempt of evil to strike it [the spirit] down.”

In Slave Religion, Al had written that the slaves looked to the book of Exodus in the Bible, forming an historical identity as an enslaved people and “creating meaning and purpose out of the chaotic and senseless experience of slavery.” Slaves believed in the future freedom of their people—even if they didn’t see it in their lifetimes. They put their hope in an end to their own Exodus, believing that “the sacred history of God’s liberation of his people would be or was being repeated in the American South.”

Perhaps yet another controversial point he made is that masters and slaves entered into a genuine religious reciprocity, “whereby blacks and whites preached to, prayed for, and converted each other in situations where the status of master and slave was, at least for the moment, suspended. In the fervor of religious worship, master and slave, white and black, could be found sharing a common event, professing a common faith and experiencing a common ecstasy.”

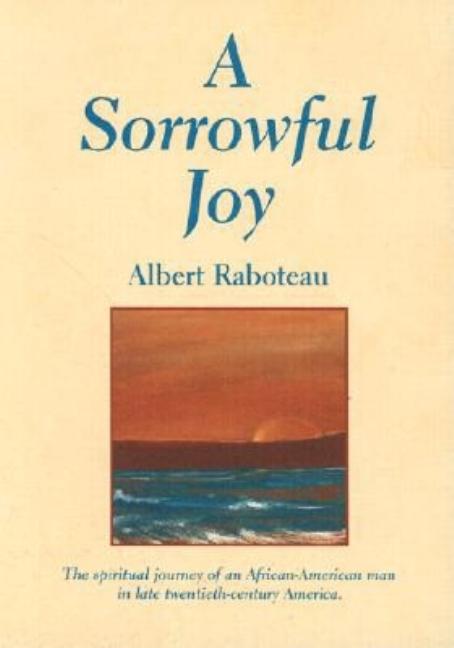

Al feared that if historians failed to see the moral and spiritual dimensions of the slave experience as authentic and liberating, even if they did not always produce political change, then key aspects of the African-American religious tradition—forgiveness and the redemptive power of suffering—would be lost. As he said in a lecture at Harvard Divinity School that was later published as a memoir entitled A Sorrowful Joy, “The primary example of suffering Christianity in this country was the experience of African-Americans.” Although it is human to fear suffering, the slaves’ experience of enduring suffering and forgiving their enemies should be remembered as a witness for all. One of the central claims of Christian is that God became man in Jesus Christ, suffering for our sins. Thus, Al reminded people that, “the suffering of Christ and the martyrs is at the center of the Christian tradition and suffering grounds the Christian to the suffering of the world. As the old slaves knew, suffering can’t be evaded, it is a mark of the authenticity of the faith.

Over several years, Al and I met for coffee numerous times—often after morning Mass at St. Paul’s Catholic Church in Princeton. Although later in life he worshiped at an Orthodox Church, Al had been raised Catholic, like me, and had a profound prayer life that included many retreats at monasteries, devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and a love of icons.

Al shared with me a video of a lecture he had given on Forgiveness in the African-American Church Experience, which chronicles numerous examples of forgiveness for evil like Stephanie’s from Slave Religion and his other books on African-American religious history.

In the question-and-answer session, one journalist retorted that the slaves who forgave their masters were still slaves. Al responded, “That’s right but that’s not their own reality. They’re not only slaves. They are children of God with spiritual power.” The slaves believed that if they did not return evil for evil, but prayed for God to convert their masters, then God would “intervene in human history to cast down the mighty and lift up the lowly.” Forgiveness doesn’t have to mean docility—it can mean trusting in God, using one’s spiritual agency to bring divine action into the world.

Al gave more contemporary examples of forgiveness in the African-American religious tradition, explaining that the Sunday School lesson on the day of the bombing of Martin Luther King’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1963, in Birmingham, Alabama, was “The Love that Forgives.” Raboteau insisted that King’s nonviolent philosophy was “not conditioned on the goodness of the other.” Rather, King believed in agape, an unstinting love that did not permit outward violence nor the inner violence of anger, hatred or even resentment. In line with many slaves and freed African-Americans that came before him, King believed that “redemptive suffering releases the divine power into human history.”

Over the years, Al and I met regularly to discuss our work, share our faith, and talk about our families. I shared with him how difficult it was to present stories like Stephanie’s about suffering and forgiveness. I didn’t want to change the meaning of her experience, yet I still hoped for a world without such horrific acts of violence, a world with justice for people who harm others. Al told me that my writing on forgiveness was important to model for others how to respond to suffering. We need to truly encounter the stories of others, he insisted, and those stories include finding meaning in suffering—a redemptive meaning.

I’ve shared the stories of redemptive suffering I’ve encountered because, like Al, I believe in the power of spiritual healing. I believe that the witness of people like Stephanie can be a balm for the wounds of others. Al’s witness as a scholar and teacher reminded me that it’s very easy to look for political responses to suffering, thereby overlooking how people find meaning and spiritual agency now in their own power, but in God’s power.

Like Al, my Catholic faith has been shaped by the stories of repentance, conversion and forgiveness I’ve heard in my scholarship. By lifting up the voices of the people I’ve met through my studies, I’ve tried to share the idea that redemptive suffering—the affirmation of the dignity of the oppressed, the power of forgiveness, and the encounter with the divine in the darkness—is a fundamental part of human experience.

So much of modern scholarship tries to avoid the experiences of the divine in the midst of suffering, perhaps out of fear of somehow justifying oppression. We can and should act to relieve the burdens of the poor, sick and oppressed. But those of us who study and teach any discipline that engages with human experience need to remember to listen carefully to the stories we hear and aim for a humanistic synthesis of knowledge, which includes the spiritual power of forgiveness and the experience of redemptive suffering.

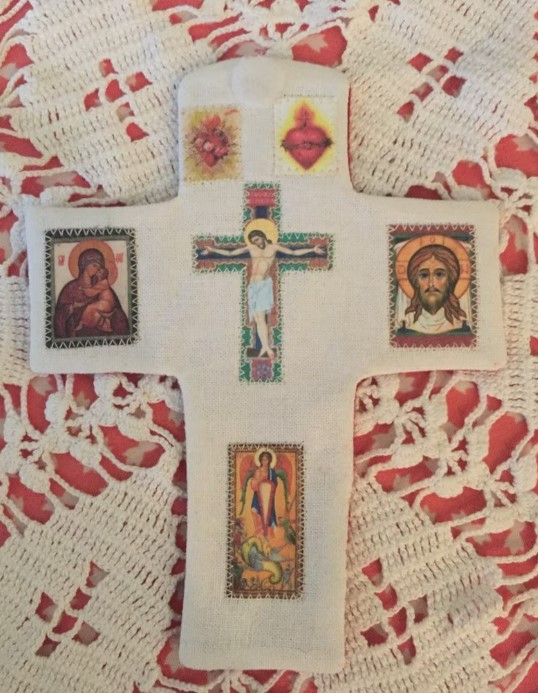

Shortly before his death in 2019, I visited Al at his home. I showed him my three favorite sacred objects: an icon of the Virgin Mary I bought in Cyprus; a pocket oratory that reproduces the typical Orthodox arrangement of icons of the incarnation, crucifixion and resurrection; and my favorite rosary, a gift from a stranger one morning St. Paul’s as I wept over the young death of a former student.

After I showed him each object, Al said, “That’s beautiful.”

Then, I chanted all of Psalm 50 in English, which reminds us that we are beggars for God’s mercy; we are saved by his grace.

“Thank you,” Al said.

“How can I pray for you?” I asked him.

Struggling to speak, Al replied, “Pray for others. Pray for the suffering.”

Then he slowly lifted his left hand and set it on mine. I leaned over and kissed his forehead. I said three Hail Marys and departed.

Al’s final words of wisdom to me—pray for those who are suffering—were a witness to his faith and a reminder of his scholarship, which shows how human action can further the action of the divine in history. Just as I prayed for Al as he was dying, all of our prayers for the suffering are, too, a way of unleashing the power of the divine into human history.

From the Al Raboteau | Forgiveness | Haiti | Martin Luther King | Sacred Art | Suffering series

View more Posts