In a recent conversation I hosted through Scala Foundation with one of the world’s leading iconographers, Aidan Hart described how shocked he was when members of a church told him they preferred to worship with white walls. Images, they thought, would get in the way of their relationship to Jesus.

Why is art—and specifically liturgical art in traditional styles such as icons—so important to worship? It is just a matter of subjective taste which art to have in churches? Does art shape our understanding the nature of the human person?

My teaching and writing often tries to explain common misunderstandings about the human person today such as:

- humans are only material;

- human consciousness is entirely a product of the social environment;

- that the basis of reality is conflict;

- it’s foolish to think that the world is full of meaning or that creation is fundamentally good.

It has taken me decades to learn that those ideas need to be fought not only with arguments, but with art.

Although the iconographic tradition that Hart writes and talks about may sound new to many people—including many devout Christians—I’m persuaded his ideas matter for our present culture because so many young people lack wonder, awe and joy. When I’ve fallen into near despair over the death of loved ones, I was mysteriously touched through art—once of the face of Jesus and once through an image of Mary.

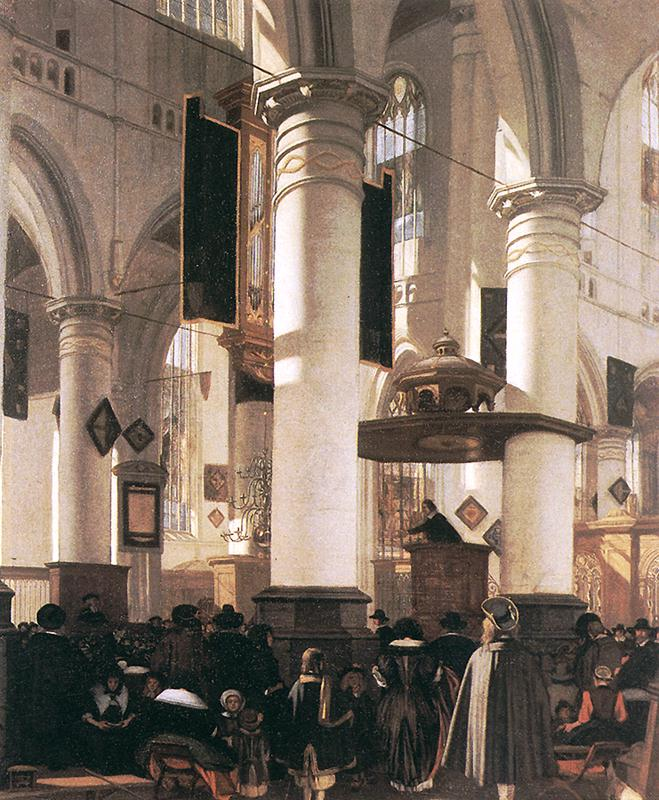

Hart explained that he was so shocked that some church members he talked to did not want art because a central claim of the Christian faith is that Jesus came to redeem us body and soul. To say that we pray to Jesus only with our minds is to deny we worship with all our senses and to deny that all of creation is capable of leading us to God.

Mis-understandings about art and faith are key to understanding larger cultural crises of loneliness, narcissism, and resentment. Iconoclasm—the idea that all religious images are hindrances to true devotion and therefore should be removed or destroyed—has been combatted several times in Christian history. It needs to be combatted again because in a world that often isn’t interested in theology or doctrine, liturgical art can speak to the heart. A void of Christian art leaves us missing a key piece of integral human formation, evangelization in faith, and cultural enrichment.

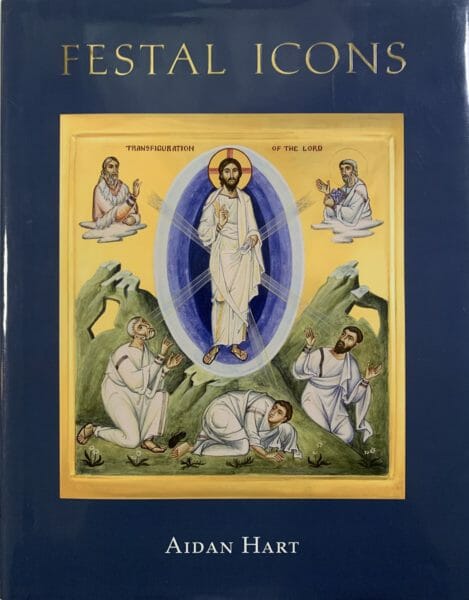

Hart’s book Festal Icons has been extremely helpful for my teaching on the Virgin Mary at Princeton Theological Seminary. In that class, we examine the connections between art, worship, culture, doctrine, tradition and identity. To know Mary, the Mother of God, is to know something about the tradition of Marian art—its form, content, and liturgical uses.

Hart is coming from the UK where he lives to Princeton to speak for Scala’s April 21-22, 2023 conference on Art, The Sacred and the Common Good, which will be held in person and also on live stream. Some of the themes of our online conversation that I hope to ponder more in depth include:

- In the early Christian church, images of Jesus and images of his mother Mary were central to expressing doctrines, such as the doctrine of the Incarnation and the Trinity. Art thus has a teaching function in Christianity. But art is more than just a form of instruction or a response to heresy. Jesus was a person with a face. We are not called only to know about God but to know God by contemplating the face of his son. The true meaning of beauty is a calling—liturgical art attracts us to God, opens our hearts, and helps us to encounter God as a person.

- If we don’t know true beauty, we can be manipulated by false beauty. The overly perfect images on Instagram calling out “Hey, look at me!” shape a competitive, oppositional identity rather than offer us shared experiences of beauty. Images designed to stimulate an immediate reaction feed a desire to possess material things rather than foster awe. In contrast to the narcissistic tendencies fed on much social media, liturgical art is humble. Whereas much of modern art tries to shock people, to grab attention by making you feel like you’ve been punched in the nose, liturgical art points us back to a tradition. Originality is not novelty. Originality is standing on the shoulders of a great tradition and being creative.

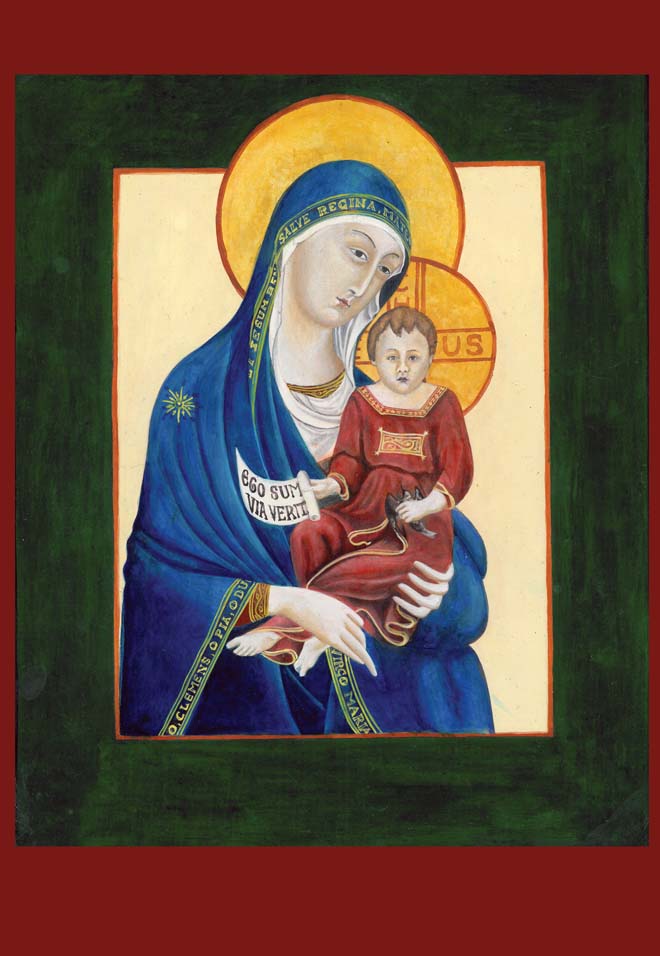

- True beauty teaches us to look at our fellow human beings as brothers and sisters participating in a larger reality, not in opposition to us. Images of Mary abound in liturgical art because Mary reminds us that the church is not a club; we are members of the body of Christ, and that body has a mother.

- Action follows vision. If we don’t have images that teach us about the beauty of life, our actions will be faulty.

How do these ideas impact your understanding of Christian art? Do you see a connection between Christian doctrine and art? How has art shaped your engagement with culture and worship?

These ideas have helped me deepen my own faith and share it. For Christmas 2022, I printed one of my husband David’s icons of the Madonna and Child onto 100 Christmas cards that I mailed to family, friends and supporters of Scala. I framed that same icon and gave it to my students of all backgrounds—Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox and seekers—who came to one of my several Christmas parties.

Who can say no to the wife of an artist when she gives you her husband’s art as a gift? Most people smiled, stared, and asked questions about it. My friend’s eight-year-old son absolutely lit up with glee. He stared at my husband in amazement because he had made something so beautiful and so meaningful.

Learning to appreciate the rich tradition of Christian art has changed my vision—as Hart explains—of who Jesus is, of who I am, and of what my calling is.

It’s not that art has had such an impact on me apart from community, prayer, and learning. It’s rather that art is an integral part of the love of learning and the desire for God. Art is an integral part of family, community and identity. Having discovered this only recently, I’m eager to share these ideas, these traditions, these images, with as many people as possible.

I hope your journey into learning about Christian art is as fruitful for you as it has been for me and many of my students.

From the Aidan Hart | Educating For Beauty & Wisdom | Sacred Art | Scala Foundation | Theotokos series

View more Posts