By Margarita Mooney Clayton, Executive Director, Scala Foundation

Note: A shortened version of this essay was published in the National Catholic Register on January 9, 2023

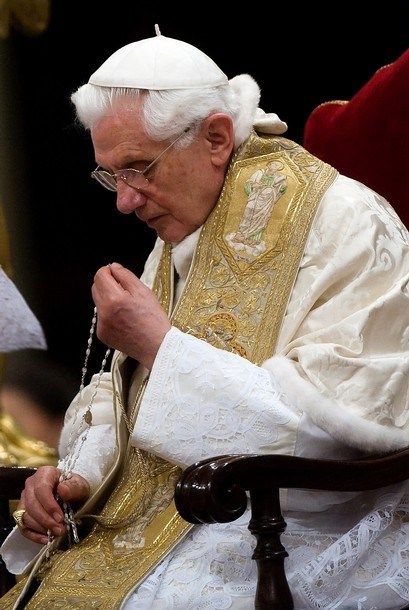

What did Pope Benedict XVI mean when he wrote that Mary is the soil of the church? Why is it so important to understand the official Catholic doctrine of reverence for Mary as so crucial to harmony in the church, the home and society?

It would be a mistake to remember Pope Benedict’s legacy as simply someone who was against church activism for the oppressed as espoused by liberation theology. As he wrote in his first encyclical Deus caritas est (God is Love) the charitable work of the church is complementary to its calling to be a home, a place of hospitality and worship at the feet of Jesus.

I’m a Catholic woman who often identifies more with Martha than Mary. Mary, the mother of Jesus, never particularly interested me as a topic of intellectual inquiry or doctrine. But after I experienced popular devotion to Mary in Haitian Catholicism, I made pilgrimages to Lourdes and Fatima where I threw myself down on my knees begging for spiritual healing. When a former student was dying of cancer, I sobbed in front of the pieta at St. Patrick’s Catholic Cathedral begging for courage to comfort his anguished mother.

What kept that childlike Marian devotion alive in me? Why did I hide it?

Climbing the professional ladder in the man’s world of academia required not just intellectual acumen but decades of strategy to get invited to present my work in prestigious places. The last thing I wanted to do was to be a successful, unmarried career woman telling other women to find their place in the church by imitating Mary.

Now, working with mostly Protestant students at Princeton Theological Seminary, I have discovered my students are curious to learn about Marian devotion and Marian theology. So, finally, in 2022, days after I got engaged to marry a wonderful man at the age of 48, I taught a class on Marian devotion to Protestants.

One student in the class was a military chaplain who had served two tours of duty in Afghanistan. “Dying soldiers on the battlefield call out to their mothers for comfort,” he told us. “Maybe Mary can teach me how to comfort the mothers of young men killed at war.”

A woman who was the mother of young twins said, “I’ve heard something about Mary crushing the head of the serpent,” she said. “I want to know more about Mary and spiritual warfare for my deliverance ministry for abused women.”

Another woman said she was married to a philosopher who valued analytical thinking above all, and he didn’t celebrate the birth of the two youngest of their four children. Raised in a church that emphasized equality between men and women, she longed for a theology that values the emotional labor of mothers. As she never felt loved by her own mother, she wondered whether Mary could model for her how to be a mother.

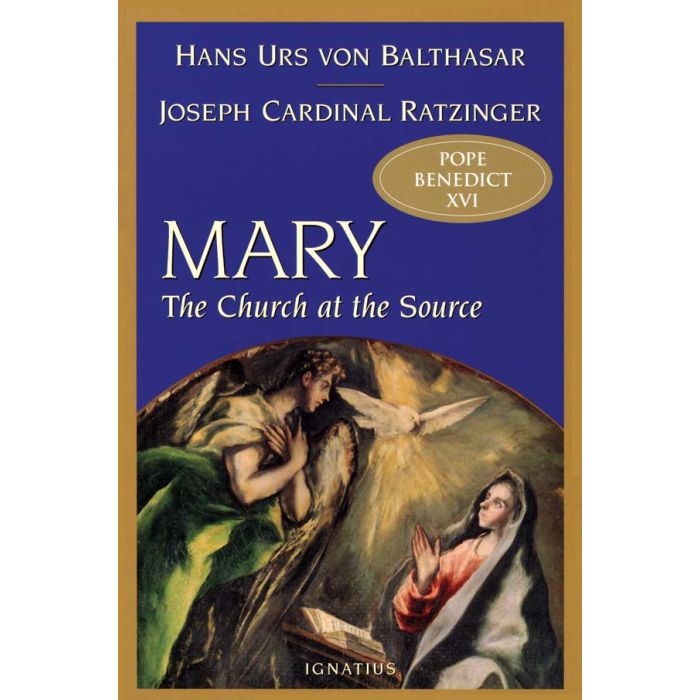

The final book we read in that course was Benedict XVI’s book, Mary: The Church at the Source. After focusing on Mary in Scripture, Mary in art, Mary in doctrine, and popular Marian devotion, we encountered Benedict XVI’s ability to integrate thousands of years of Marian doctrine and devotion with clarity, brevity and intelligibility.

Three lessons I have learned from Benedict XVI’s writings on Mary are part of his legacy to the universal church.

First Lesson: No Mary, No Church

One of the threats to the Church that Benedict XVI named is the call to change the world. “Producing the world oneself,” Benedict XVI cautioned, leads to a shallow activism that refuses to bow down and pray for God’s grace.

“When making becomes autonomous,” Benedict XVI wrote, “the things we cannot make but that are alive and need time to mature can no longer survive…What we need then, is to abandon this one-sided, Western activist outlook, lest we degrade the Church to a product of our design and creation.”

I shifted from sociology into theology because I longed to be both a professor and a spiritual mother. I saw that, while activism abounds in the academy, the church alone can offer spiritual healing. The church is a home. Mary is the soil of the Church. No Mary, no foundation. No Mary, no home for the wounded. No Mary, and the Church becomes nothing but a political organization.

Second Lesson: No Marian Devotion, No Reverence for Women and Mothers

What are we to make of the fact that Jesus spent decades subject to the authority of the home? So much of theology wants to focus on Jesus’s divinity or his public ministry and teachings.

“Only the Marian dimension secures the place of affectivity in faith and thus ensures a fully human correspondence to the reality of the incarnate Logos,” Benedict XVI writes. Only a faith that is both rational and affective will lead us out of gender warfare and back to embracing “the living mystery of maternity and of the bridal love that makes maternity possible.”

We cannot understand what it means to be born anew, to be a child of God, simply metaphorically. We are born into families; the faith is passed on person to person; the church herself has personality as the bride of Christ. I needed encouragement to embrace spiritual motherhood as a single woman who became a bride at 48.

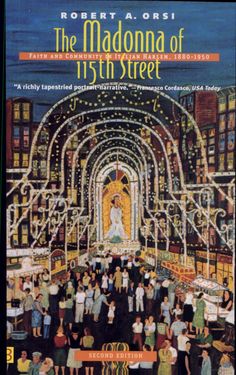

Men and women in my classes are moved by books like Robert Orsi’s Madonna of 115th Street, which recounts Italian reverence for family matriarchs and Mary. Women in my classes read with awe about the often-quiet maternal power in Italian homes and the home of Jesus. Italian men had public authority, but women ruled the home, which matters more. Jesus subjected his authority to Mary’s at the wedding of Cana.

Marian affection ensures the bond with God is also from the heart—something that as an academic I often suppressed. I had to fight not to resent women who are more feminine than me, more nurturing, more emotionally intuitive. All women—those with children and those without—are called to spiritual motherhood, an often-quiet moral power men should revere.

Third Lesson: Mo Mary in Liturgy and No Marian feasts, No Holy Priests

I have often wondered why arguments for women’s ordination are framed as a restitution for a kind of class warfare extended to men and women in the church. Men and women in the church need harmony that respects the mystery of each sex.

Although I have met men—including priests—who do not seem to respect women’s authority, I have met many more priests who profoundly respect women. Anyone blessed to have known a holy priest—and I have known many—knows the sacrifices, wisdom, and courage it takes to minister faithfully in today’s world.

Priests need to be encouraged to celebrate the Eucharist as central to everything else they do. We need the sacraments of the church to be celebrated reverently.

Liturgy is not about the priest, it is about the Eucharistic feast. And the liturgical calendar is filled with Marian feasts—the Assumption, the Queenship of Mary, etc. In liturgical hymns such as Alma redemptoris mater we sing doctrine—reminding us that the church’s doctrine is meant to be a jubilant worship of praise before the mystery of God being revealed in time, through a woman.

My Protestant students admire how Benedict XVI links Marian mysteries in the Bible to the liturgical calendar, an often-forgotten aspect of Christian tradition. Reviving feasts and hymns celebrating Mary in Scripture can help make dogmas like Mary, the Mother of God, new again.

I was taught Marian devotion at St. John’s Catholic School in Frederick, Maryland. But I left behind Marian devotion in college and embraced an activist mentality. When my father was near death when I was 27, I was unable to get to his bedside. I was too distraught to form any pious thoughts or words. Sobbing in the middle of the night, I grabbed a rosary and called out to Mary, “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with you. Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb.”

An image of Jesus on the wall behind the helm of a boat glowed in the darkness of my room as I repeated those words again and again.

When Benedict XVI died on December 31, 2022, I have no doubt that Mother Mary showed him to his eternal home.

It was through my work for the lonely, the addicted, the abused and neglected, for the sick and suffering—whether that be in Haiti, Nicaragua, rural America or the classrooms of the Ivy League—that I learned the wisdom of Benedict XVI’s Mariology as an antidote to a pride-filled activism. I have found greater inner peace by not giving in to Martha’s anxiety about the work I’m called to do. By committing to a life of prayer, I have grown in my capacity for spiritual motherhood.

For those in bondage to spiritual darkness; for my students discerning vocations to ministry; for unappreciated mothers and wives; for Catholic priests who struggle with temptations to violate their vocations, I pray many times every day a prayer I suspect in Benedict XVI’s heart as he neared death. It’s a prayer that expresses a central Marian dogma, praises Mary and begs for her earthly and eternal help:

“Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.”

From the Benedict XVI | Church | Drug addiction | Justice | Marian Devotion | Mother of God | Priests | Religious processions | Virgin Mary | Women series

View more Posts