Looking At Rabanus Maurus, St Dunstan, the Anonymous Painter of the San Damiano Crucifix, and Matthew Paris: How They Are Connected and What They Can Teach Us Today.

Recently I was put in touch with a small group of artists at the recently established sacred art studio at Ealing Abbey, the Benedictine Abbey in West London. This is a group of artists who are learning their craft under the ultimate guidance of Aidan Hart, the British iconographer. They are seeking to establish a group that learns together and passes on what they learn and as they learn it, to others so as to encourage the spread of the iconographic tradition in the Roman Church.

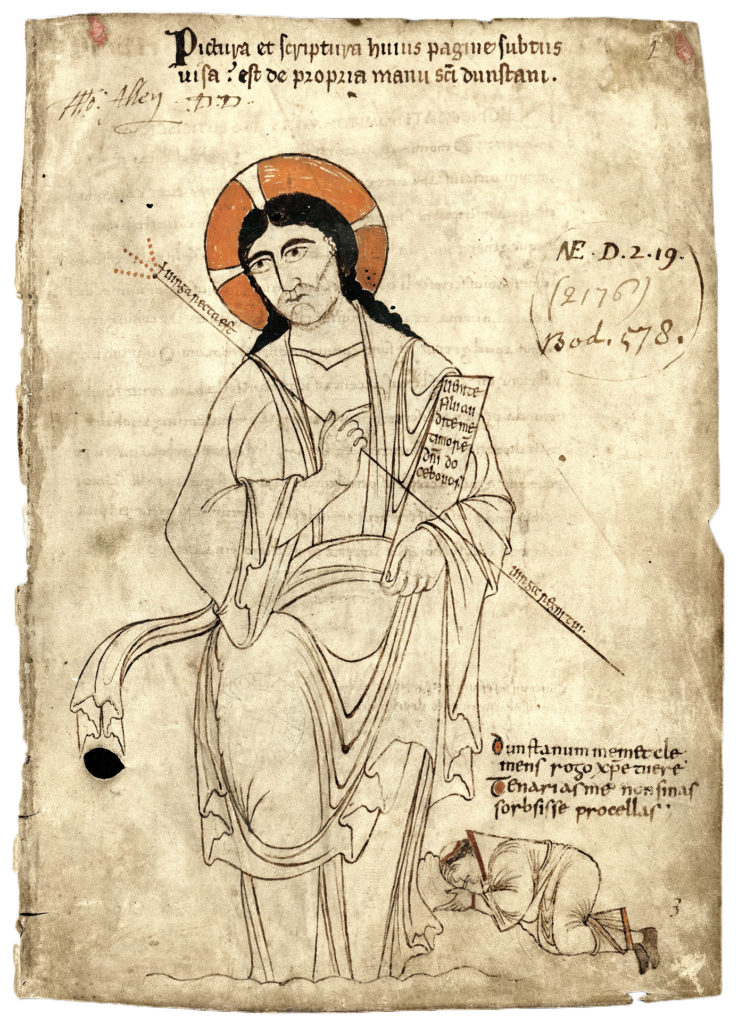

I was interested to talk to them about their vision of the forms of iconography from the past that might appeal to the modern eye, and so help act a launch pad for what might in time be the development of a distinct contemporary, but nevertheless authentic, tradition of iconography for today in the Roman Church. I was enthusiastic to learn that they shared my enthusiasm for the line-based Romanesque and early Gothic styles of the English Church. (Regular readers will be aware that I tend to focus on the work of the 13th-century gothic artist Matthew Paris.) The artists of the Ealing Abbey studio directed my attention to the work, previously unkown to me, of St Dunstan, who lived in the 10th century. St Dunstan is known as a reformer of English monasticism who was based in Glastonbury for a large part of his life. He is less known as an artist. Here is his drawing of Christ in which he has painted himself adoring the Saviour.

The inscription above the monk reads: Dunstatum memet clemens rogo, Christe, tuere. Tenarias me non sinas sorbsisse procellas (I ask you merciful Christ, to watch over me, Dunstan, and that you do not let the Taenarian storms swallow me.)

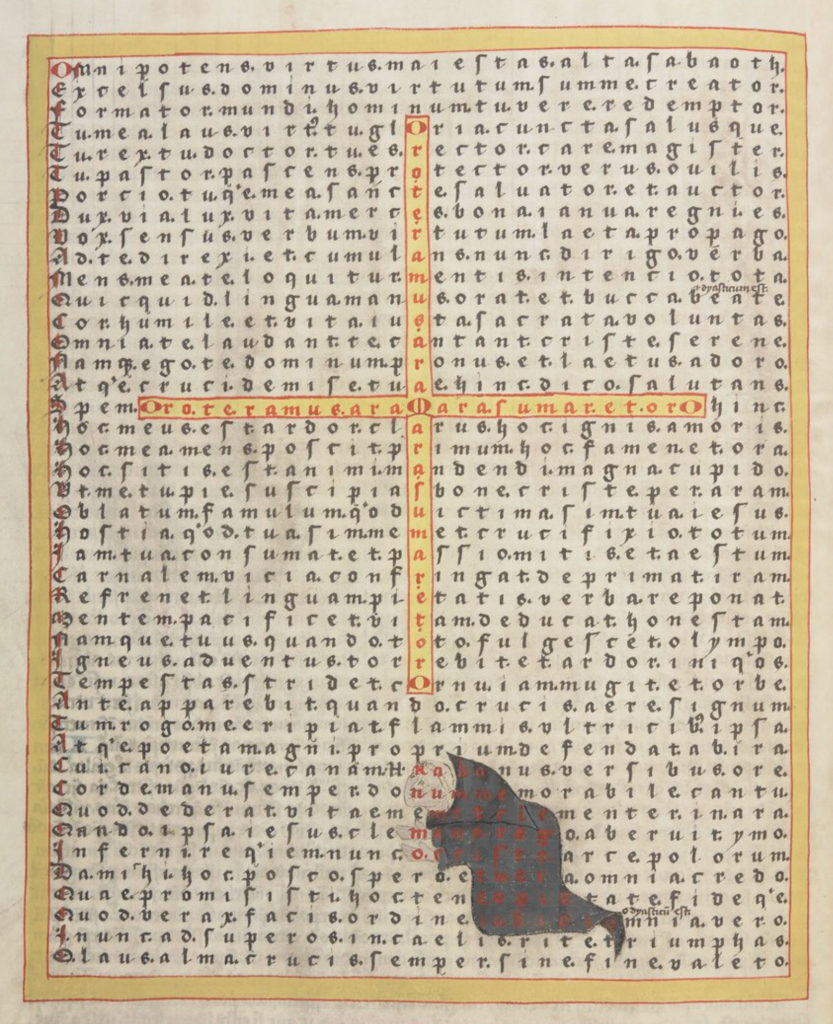

In their book The Image of St Dunstan, authors Nigel Ramsay and Margaret Sparks suggest that the idea for placing himself in the image comes to St Dunstan from a 9th-century manuscript by another monk, Rabanus Maurus. Maurus wrote and illuminated a poem, De laudibus sanctae crucis (“The praise of holy cross”), a collection of manuscript poems presenting the sacred symbol in words, images, and numbers. One of the illuminated poems (in which every line has the same number of letters) can be seen here:

As we can see, Rabanus Maurus portrayed himself adoring the cross.

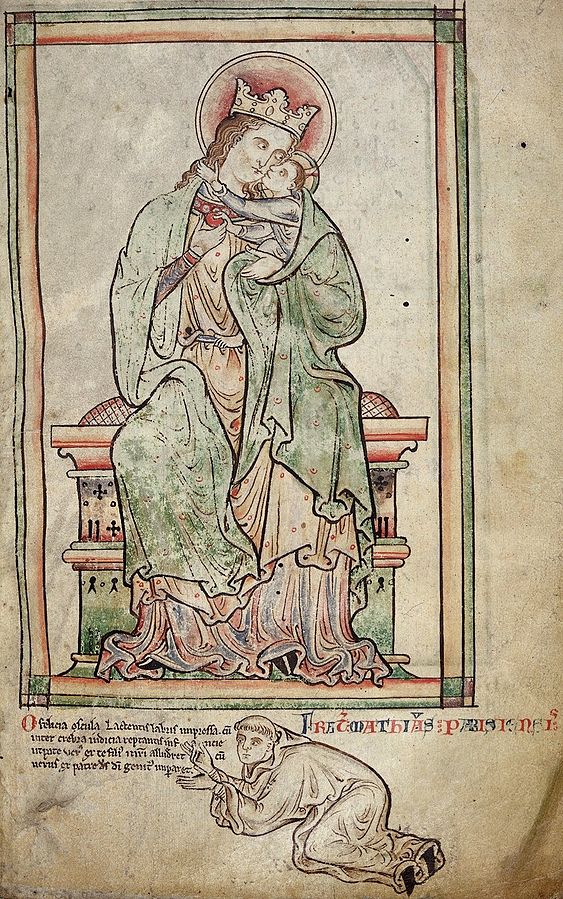

When I looked at the St Dunstan image. It immediately brought to mind two others. First was from the 13th-century England and by the monk Matthew Paris:

Here Paris has referred to himself as -‘Frat[er] Mathias Parisiensi[s]’- Brother Matthew Paris. It might be that Paris got the idea of including himself from Dunstan, who first got the idea from Maurus, I cannot say. But it occurs to me that it is as likely that all three, Maurus, St Dunstan and Paris are working within a tradition in which the scribe portrays himself humbling himself before a holy patron. This being the case it might be that none is aware of the work of any of their predecessors directly.

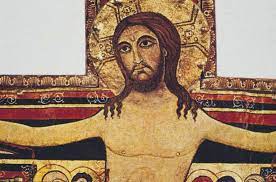

Another connection that occurred to me as I look at the St Dunstan image is that of the San Damiano crucifixion in the Basilica of St Francis in Assisi, in Umbria, Italy.

The facial features of each are striking, to me at least, as being similar to the other. I had always been under the impression that the San Damiano crucifixion had its origins in 9th century Syria, but most references I can find nowadays seem to have revised that idea and no suggest that it was painted by an Italian artist in the 12th century. So assuming the latter to be true, we might ask when the 12th century artists saw the St Dunstan image? Or are both following a established tradition for what the face of Christ looks like, with each being aware of a number of similar images.

Again I do not know the answer to this question.

What does seem to be apparent, however, is that artists in the past, were looking at each others’ work and happily replicating and adapting what they saw in order to create their own work. This is good practice for it is the means by which tradition is passed on.

Following traditional forms in art is almost antithetical to the modern mindset by which everyone tries to be different from those who preceded them in order to demonstrate ‘originality’. However, as Christians, until we re-establish a mindset by which artists copy each other’s works with understanding and deliberatelyseek to adapt or change only what is necessary to meet the needs of their commission, we cannot re-establish a sacred art tradition in the Church today. A hermeneutic that dictates that artists do as little original work as possible (rather than as much as they can), is one that respects the past and, paradoxically, allows for the development of steadily better work in the future. In this sense tradition has its hands on the tiller that guides present day artists as they develop new and inspired work.

So whichever works from the past eventurally do inspire the new tradition of the future, it will take a team of artists who view themselves as humble scribes, in the manner of Paris, Dunstan and Maurus, rather than feted original geniuses for it to happen!

From the Matthew Paris | Rabanus Maurus | St Dunstan series

View more Posts